Much like the saying ‘familiarity breeds contempt,’ we often take for granted the things that shape our daily lives—whether it’s the ease of the smartphone, our daily use of electricity, or even something as simple as toilet paper. There was, however, great skepticism and resistance toward these goods when they were first introduced to the public. Similarly, we rarely stop to reflect on what’s been achieved throughout history. As I read through the pages of this book, B. B. Keet, from the Institute for Reformation in South Africa, I was reminded that the same is true of my own South African heritage. I was struck by my ignorance of our cultural and spiritual heritage; and how oblivious I am to the battles fought by men and women who helped shape our great nation and faith.

We often take for granted the things that shape our daily lives.

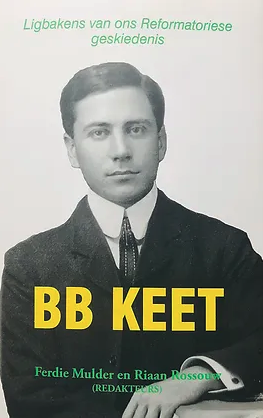

Bennie Keet was one of those faithful figures. He’s a man very likely unknown outside a small group of historians, theologians and descendants. And that needs to be remedied. This book goes some way towards doing that, as I hope my review will too.

The New South Africa and Our Old Faith

South Africa’s transformation as a nation is often viewed through the lens of political struggle. But men like B. B. Keet remind us that religious voices played an equally vital role. This biography is part of a series titled Beacons of Light From Our Reformed History, which focus on some of the struggles that great men and women of God have faced in their defence of the true gospel. Typically those struggles were bound to political and societal upheaval. So this book serves as a great reminder that those struggles belong to us all. To the church.

Like those Christians mentioned, I’ve taken my heritage for granted.

As the authors write, “For most Afrikaans Christians, there is no longer a healthy relationship with their Afrikaans Reformed history. A rich history that we can use to strengthen our faith and which urges us to live faithfully in the new South Africa” (p12). Their argument, then, and purpose for this book is a challenging one. Like those many Christians mentioned, I’ve taken that heritage for granted myself. The picture of B. B. Keet’s life and his refusal of the status quo (state sanctioned racism) connects at many points with the realities facing believers today.

B. B. Keet

Ferdie Mulder and Riaan Rossouw

B. B. Keet

Ferdie Mulder and Riaan Rossouw

Starting in the 1930s, many of those in the Afrikaans and Reformed churches across South Africa endorsed Apartheid with the help of the Bible. One of the men who opposed those gross abuses was Professor B. B. Keet. He insisted that while God’s word is inspired, it couldn’t be used to support the atrocities that took place in South Africa. He appealed to God’s authoritative word in arguing against them.

Today the Bible is being “dynamically” reinterpreted in other ways, lending support to radical feminism and the LGBTQI+ movement. B. B. Keet’s unwavering loyalty to God’s truth is a call for us, living some 100 years later, to resist compromise and reject widely accepted misuse of the scriptures.

Let God Speak

Let me say, before going any further, a danger exists here. We must be very careful not to become nationalistic concerning our South African heritage. There is little to be proud about. Too few people opposed the Apartheid regime, often confusing it with patriotism and the protection of cultural goods. Furthermore, we mustn’t forget that this regime was supported by scripture. Well, so-called biblical principles. Many South Africans found those convincing.

B. B. Keet knew the regime did a terrible disservice to God’s word.

However, Keet’s story reminds us that not everyone was persuaded. For together with a small minority he knew the regime did a terrible disservice to God’s word and people made in God’s image. For Keet, “the question is not, in fact, how we can justify our attitude to life from the holy scripture, but rather, what our attitude to life must be to be able to pass the test of the scripture” (p76). In other words, we shouldn’t turn to the Bible to endorse how we live. It isn’t given to justify however we choose to live. No. God’s word must inform and shape how we live.

Therefore, in his own time, Keet sought to demonstrate that the Bible couldn’t be used to support Apartheid—and any racism, for that matter. Societies become distorted when they worship gods of their own making. Like him, we should insist on permitting God to speak in scripture. “Keet rejected the biblical defence of Apartheid from the infallibility of the word of God and warned the church seriously and urgently about it” (p76).

A New Age and Old Errors

Of course, Apartheid was only the devastating tip of the theological iceberg that would become prevalent over the years. So Keet insisted that the fundamental issue wasn’t about finding biblical support for predetermined positions—whether Apartheid then or our own current social issues. When we come to the Bible, he argued, it should radically reshape our perspectives.

Today the church faces pressure on every front from various ideologies.

This is an important corrective and relevant principle for us today. For the church faces pressure on almost every front from various ideologies. Two that are perhaps particularly noteworthy are Marxism (critical theory) and expressive individualism. The former prioritises and interprets everything along power dynamics and group identities, reducing biblical truth to a tool for social analysis rather than God’s authoritative truth. It majors in societal transformation rather than transformation of the heart. The latter is in some ways a modern iteration of hedonism, where the individual, their happiness and self-fulfilment is prioritised above all else.

The result of both the above is that the church maintains biblical language but its meaning is fundamentally changed. Contemporary values are smuggled in while God’s are abandoned. To this point, Keet writes “our conclusion is therefore that the highest goal of man is not to be happy, but to live in accordance with the holy law of God out of love for his glory” (p198).

Will You Stand Firm?

Like Keet, I studied theology at the University of Stellenbosch—unlike him I didn’t become a professor there. Though we studied almost a century apart from each other, there are similarities in our struggles at university and after. Keet found himself up against the ideological force of his day (Apartheid), which had hijacked the Bible for its purposes. He rejected his culture in favour of God’s authoritative word. Likewise, Christians today must resist being conformed to the world and instead must be transformed by the gospel (Romans 12:1-2).

Keet’s biography is a reminder that there are still Christians for whom the true gospel is worth defending.

Keet’s biography is more than an interesting piece of South Africa’s history. It’s a reminder that there are still men and women for whom the true gospel is worth defending. In this way, Keet’s life and writing is in continuation with other Reformed greats, such as Luther, Calvin, Whitefield, Edwards, Owen, and Bunyan. Only, let’s remember, the greatness of those men—including Keet—lies in the fact that they didn’t seek out greatness. They didn’t court their culture or clamor to be accepted by the crowd. Rather they sought to know God intimately and preach him faithfully.

Keet leaves us with a challenge much like Paul’s in 2 Thessalonians 2:15. Will we, like them, “stand firm and hold fast to the teachings that were passed on to us”? Let us strive then not only to appreciate this legacy, but embody it. The Christian faith isn’t great because of its relevance but because of God’s unchanging truths and promises.